Ludeme

Ludemes are a way to dissect games into their smallest meaningful parts. Many of these systems exists, but most of the concentrate on how to analyse or how to design a game. Ludemes also take the semiosis of the player into account: How is the player making sense of the video game, and how are these smallest parts working together to enable the player to have a meaningful experience?

In Conceptualisation

“To summarise, a ludeme or “ludic meme” is a fundamental unit of play, often equivalent to a “rule” of play; the conceptual equivalent of a material component of a game. A notable characteristic is its mimetic property - that is, its ability and propensity to pass from one game or class of game to another.” (Parlett, 2006)

“Importantly, he observes that ludemes must be contrastive, that is, changing a ludeme within a game should produce a change in its play.” (Browne, p. 1)

The part on contrastiveness is insofar important as Parlett distinguishes between ludeme and instrument of play, e.g. the rule of movement and the piece of chess1. That means, we must consider formal elements. The piece of chess can be exchanged with anything else, as long as its specific rule of movement is still attachable to it. Meanwhile, the color of the piece can’t be changed from one to the other (black/white) without affecting game mechanics. The limits of a ludeme’s contrastiveness is set by its memetic aspect. Being of memetic nature, ludemes must be learnable/recognizable through play and vision, whereas its materialization can differ. Different kinds of code can produce the same kind of ludeme.

“Ce faisant, l’amateur constitue en tant qu’unité discrète un ensemble d’éléments qui peuvent très bien être dispersés sur le plan de la programmation – toutes les lignes de code se rapportant au fonctionnement du bloc ne sont pas nécessairement regroupées.” (Hurel, 2020, p. 191)

Browne defines four essential aspects of ludemes

- Discrete (must be describable in simple terms, and discernible from other minimal units of play)

- Transferable (like memes)

- Contrastive (see above; change to ludeme should bring change to gameplay)

- Compound (can be composed of simpler sub-units, or part of a larger super-unit)

He also describes the different perspectives one can take on ludemes, respectively what different kind of models exist on it.

- Memetic model (ludemes as game memes)

- Emic model (smallest unit of something in a system; like phoneme in speech or morpheme in meaning; see In Language)

- Video game model (emerged independently of prior discourse; smallest loops of engagement)

- Ludemic model: “The ludemic model of games is a computational method for describing games by their component elements, each of which is implemented in a corresponding piece of computer code (Browne, 2009).” (Browne, p. 10)

Browne finally comes up with the following definition. It is insofar interesting to note that Browne explicitly states that this definition is partially grown out of his experience of being a programmer (see Conceptualizing Programming) and he “agrees almost exactly with Parlett’s 2006 description except for the observation that the equipment and components of a game should also be considered ludemes if they have a functional impact on play” (Browne, p. 16). The latter is an important distinction to being a hardliner on the contrastiveness of a ludeme.

“A ludeme is a discrete unit of information relevant to any game, which may be atomic or compound in nature, and which can be readily transferred between games to change the function of the game in at least one plausible case.” (Browne, p. 16)

An aspect that Parlett did not approach and Browne calls contested, but Hurel and Arsenault were quick to point out, is that ludemes need to be part of larger assemblages to become meaningful in regards of gameplay.

“Avec les ludèmes, comme le dit Pierre-Yves, une plaque au sol n’a pas de sens, il faut encore une porte fermée, un Link, une statue dans le coin, la capacité de tirer/pousser. C’est donc une configuration de plusieurs éléments qui devient le seuil minimal à partir duquel il y a du sens. On est déjà à un niveau équivalent à morphèmes, morphèmes en mots, mots en relation dans une phrase par une syntaxe.” (Arsenault, 2024)

Browne goes into that direction with the compound aspect, but goes only as far as saying, that ludemes can be constructed of smaller ludemes. It’s probably a purely ludological approach to ludmes.

In Code

Hurel highlights how ludemes, in the case of amateur video game developers, create a bridge between play and the games technological foundation.

“Ces unités minimales de jeu sont selon nous la prise par excellence de l’amateur, parce qu’elles se situent « à niveau de joueur » : elles fonctionnent comme de petites unités reconnaissables depuis le jeu comme depuis la création. Pour cette raison, elles ont une fonction d’interface : analyser le fonctionnement précis d’un bloc à pousser, c’est déjà presque mettre au jour les lignes de programmation et, inversement, assembler des lignes de programmation pour former un bloc à pousser, c’est déjà chercher à produire un élément jouable. Or, comme nous l’avons vu, nos informateurs agissent comme des amateurs qui passent de joueur à créateur. La matérialité double du jeu vidéo, à la fois formes-prêtes-à-être-jouées et lignes-de-code-dissimulées prend alors toute son importance.” (Hurel, 2020, p. 196)

A quote from an interview displays how a versed developer can imagine how a gameplay situation or a ludeme is (or has to be) manifested in code.

“Quand tu imagines un gameplay en fait tu imagines un algorithme. (Francis)” (Hurel, 2020, p. 196)

This has important implications in conceptualizing ludemes as manifestations of the Computational Image of Berry, the concrete thing that translates code ontologies into player phenomenologies.

“Tracing the early history of video game visuality in programming practices” whereas visuality is the socio-cultural construction of what and how we see. Ludemes, applied to video game development history, become video game developers’ conceptual vocabulary for conceptualisation of video game designs. An interesting take on this are demakes. They often introduce newer ludemes and game mechanics to older systems. The problem was not, that newer games were not possible on older systems, but that game developers did not have a conceptual vocabulary to come up with them.

As a unit of gameplay

I am quite fond of ludemes outlined and defined through Browne and expanded on by Hurel. I do feel the necessity to stress the importance of ludemes’ need to be embeded in ludic situations. A ludeme on it’s own does little to nothing. It needs to be materialy manifested in any way, and be part of a larger conglomerate of ludemes and para-ludemic elements. Otherwise, the ludeme degenerates to a ludo-deterministic perspective.

I would argue, that a game usually contains an element of uncertainty (even if it is narratologically linear). If I start a game, I’m not sure about the outcome. This uncertainty is in parts enabled by ludemes, that form complex or emergent ludic situations, that allow a player to experience it. In a best case scenario the balance of the game is just right to keep up the uncertainty until the outcome is manifested.

Arno Görgen described this aspect as follows:

Wenn du von Spielen als Akt sprichst, würde ich sagen, dass der Outcome oder das konkrete Spielen kontingent sind und der Spieloutcome trotz aller Antizipation von einem Moment der Ungewissheit begleitet wird. Die Software dient also rein funktional dazu, Hindernisse zu generieren und Copingstrategien der Spielerinnen zu evaluieren und darauf zu reagieren. Andere Software ist im normalfall auf das Gegenteil angelegt, Kontingenz in der Interaktion ist da von Seiten der Userinnen unerwünscht.

This is also to say, how important embodiment is for a ludeme to be a ludic micro-element. In a ludo-deterministic perspective, one of the chess teams could have any color, as long as the two teams have to different colors. But from a players perspective, it phenomenologically matters if that color is black or pink, or every figure has each its own random color except the one of the enemy team.

Also see Games Built the Computer: Babbage, Lovelace and the Dawn of the Ludic Age

In Linguistics

Dominic Arsenault made some excellent and valid points in a private conversation, regarding how ludemes behave to language.

L’idée des ludèmes est bonne, mais je ne suis pas chaud à ces systèmes. C’est le même problème avec les game design patterns (Holopainen), les briques de gameplay (Alvarez & Djaouti et…?), etc. J’en parlais un peu dans ma thèse doctorale je crois, mais mon opinion reste assez semblable depuis une douzaine d’années là-dessus. Je crois que le langage est une forme de structuration qui n’est pas aussi versatile et applicable à d’autres domaines que beaucoup de théoriciens le pensent. Je crois que le cinéma n’est pas un langage. Là-dessus je suis David Bordwell, qui en parle bien dans un chapitre de Avatars of Story (ou Narrative across media?) de Marie-Laure Ryan; il parle de la narratologie néo-structuraliste et de la tendance à voir des unités ou configurations filmiques comme des éléments de langage, des verbes, des phonèmes, des morphèmes. On revient à Metz et Le cinéma, langue ou langage? Pour Bordwell, il n’y a pas de signification stable et unique à un phénomène cinématographique (i.e. un flou ne veut pas dire “vision brouillée du protagoniste”, il y a des flous dans des paysages sans sujet regardant, des flous qui s’ajustent pour simuler l’attention visuelle du protagoniste, des flous artistiques, etc.) et il faut toujours remettre les éléments en contexte, car l’usage vient avec le contexte et il n’y a pas de sens fixe et transposable.

Je ne crois pas qu’il y ait une stabilité incompressible dans les éléments qu’on peut appeler des ludèmes. Un morphème est une unité minimale de sens. Mais il porte un sens, et ce sens est univoque; c’est la combinaison des morphèmes en mots, puis des mots en phrases par la syntaxe, qui génère une pluralité de sens qui demande l’interprétation. Avec les ludèmes, comme le dit Pierre-Yves, une plaque au sol n’a pas de sens, il faut encore une porte fermée, un Link, une statue dans le coin, la capacité de tirer/pousser. C’est donc une configuration de plusieurs éléments qui devient le seuil minimal à partir duquel il y a du sens. On est déjà à un niveau équivalent à morphèmes, morphèmes en mots, mots en relation dans une phrase par une syntaxe.

C’est un peu la même chose avec les images; un trait sur une toile n’est pas une unité de signification qui a un sens stable qui en est la racine comme un morphème, c’est un trait sur une toile, et ça peut signifier une foule de choses différentes selon le contexte et le reste de l’oeuvre. Il n’y a pas de stabilité univoque du sens au niveau de l’unité.

Nonetheless, Damien Hansen approaches ludemes via linguistics and semiotics. In Parler le jeu vidéo he starts by outlining all the different approaches that tried to define a video game’s smallest parts, as Arsenault touched on. A key critique of Hansen is that these systems of small parts were most often applied towards categorization of video games or meant as basis on how to design good video games. These approaches most often than focused on rules and mechanics. And, while acknowledging their existence, they also left the concrete elements as well as the player experience untreated.

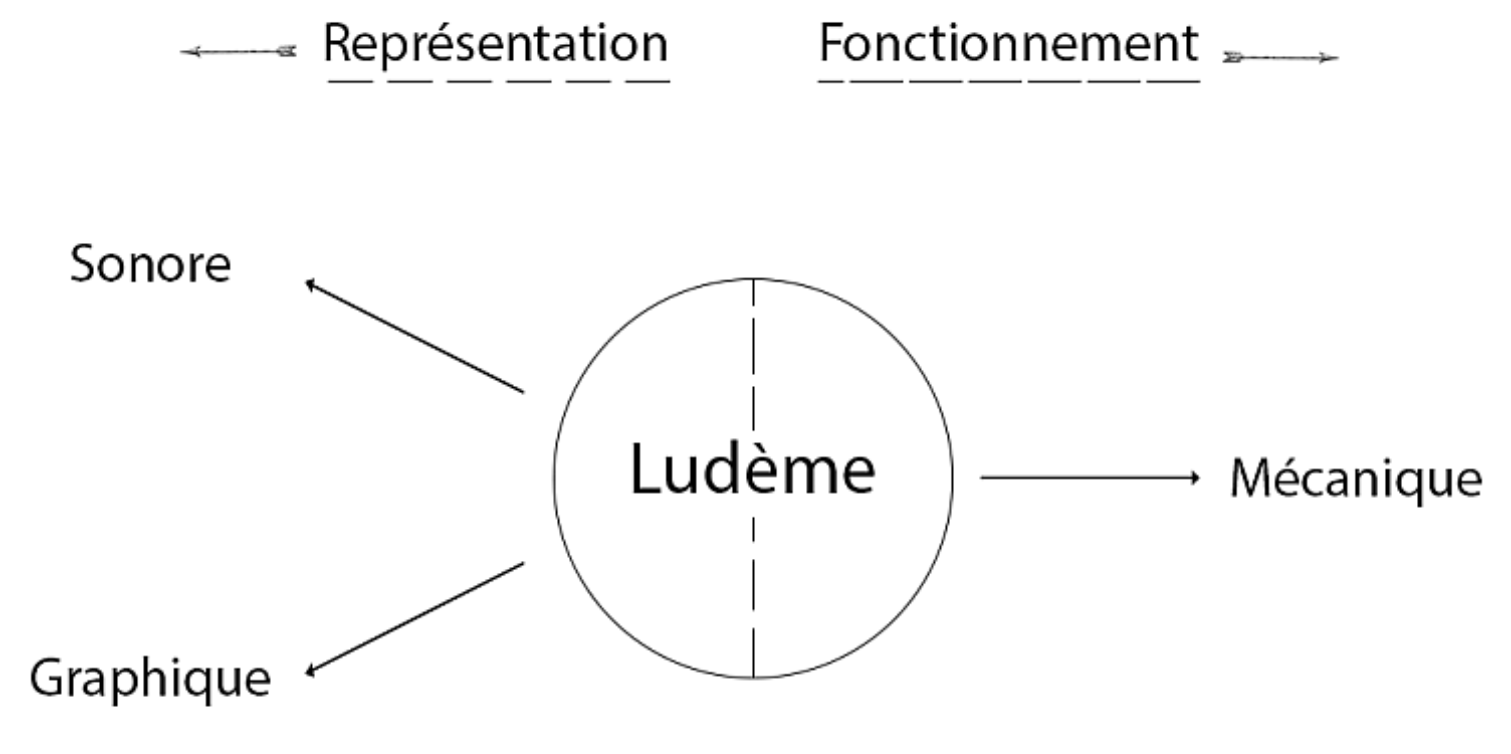

A concrete element finds its equivalent in Parlett’s instrument of play, or Crawford’s nouns. Hansen argues that to be meaningful, ludemes must be instantiated through concrete elements. Next to a mechanic, rule or element of interaction (mecanème) a ludeme has a representation made from a visual and/or an audible aspect (graphème and acoustème). These three aspects are then composing (composants) the ludeme. This indicates that Hansen layers the elements shifted by one level, compared to Arsenault, which likes ludemes to morphemes.

Diagram of ludeme

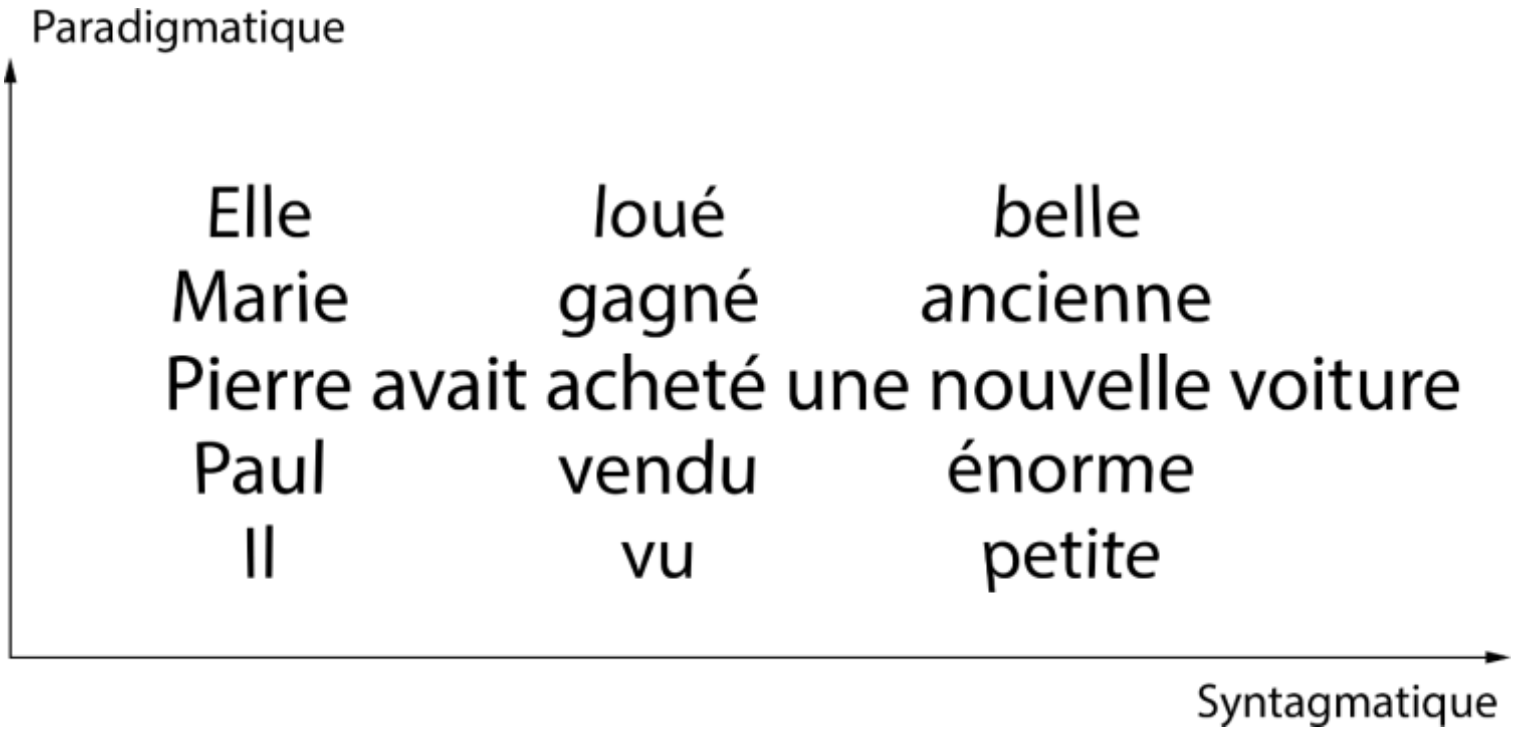

Hansen approaches the matter of dissecting a video game via meaning making (semiosis) and take the aforementioned critique into account. As Arsenault pointed out, the singular elements aren’t sufficient by themselves, but need to be considered in relation to each other. The way these relations are structured is taken through the concept of syntax, by Hansen. The book sets out by introducing the syntagmatic (Propp, syntax) and paradigmatic (Lévi-Strauss) analysis of texts. The syntax describes how the singular elements have to be ordered to create a meaningful consumption. The paradigmatic axis indicates that the singular elements on the syntagmatic axis can have alternatives or variants.

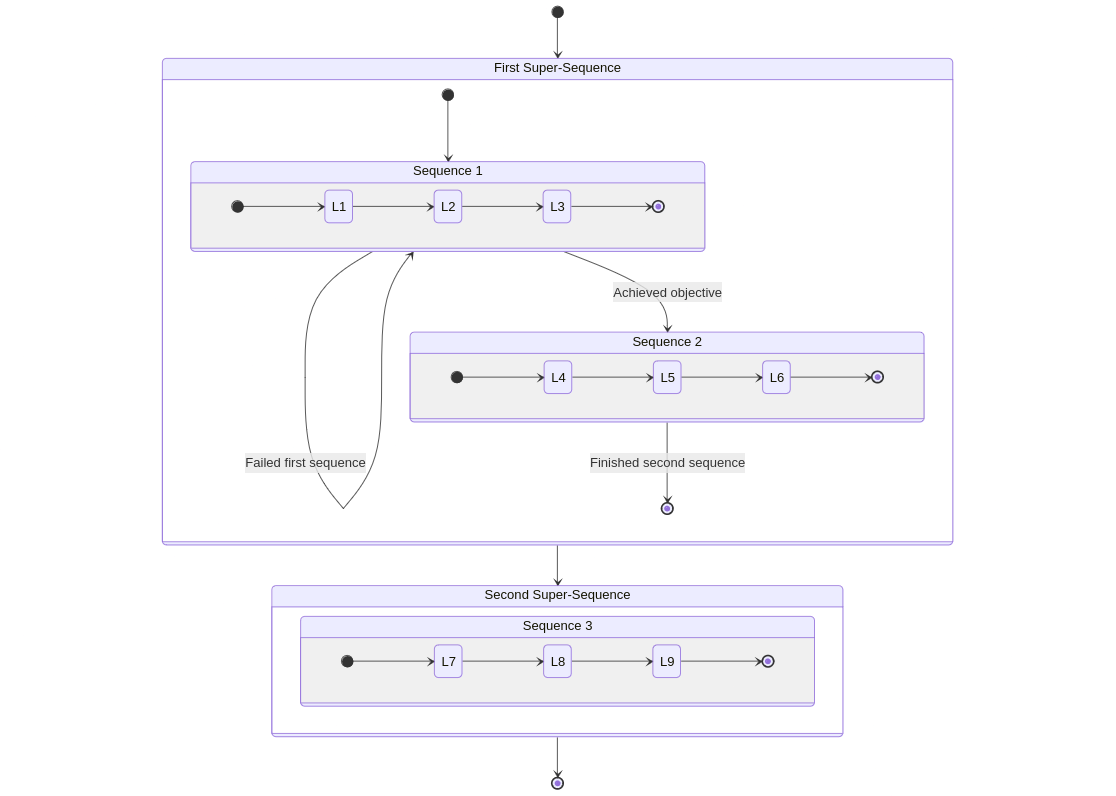

Several ludemes, thus structured, must then be organized in larger unites. In linguistics this would be sentences, paragraphs and whole texts, or motifèmes, the latter referring to a narrative proposition. Such a super structure amounts to objectives ordered in a logical sequence, the consecutive reading of which would tell the game. Other approaches found this super structure in concepts like missions, maps and areas, objectives or the game-loop. Hansen introduces the term sequence to outline this organizational unit, and hands it the ability to be recursive, meaning a sequence can be part of a larger sequence. He also mentions that their model is geared at the lower-mid levels of analysis and description.

Example diagram of sequences

Comparison of terms

| Level | Linguistic | Hansen | Cousins | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire Object | - | Division Récursive (Sequence) | Entire Game | |

| Syntax | Motifème | Sequence | Levels; Mission; Mission Elements | Areas, Game-Loop, Objectifs |

| Significatif | Kinème | Ludeme | Primary Elements | Verbes, Atoms of Choice |

| Distinctif | Morphème | Acoustème, Graphème, Mecanème (Composants) |

Further important aspects

- Hansen highlights the importance of uncertainty (incertitude) for game design and player experience

- Further, the ways ludemes as cultural codes are acquired is an important question to be asked in future analysis

- Finally, he proposes a ludic analysis along playing the game and describing how one interacts with different ludemes. Instead of trying to create an inventory of ludemes beforehand.

Also see Parler le jeu vidéo : Le ludème comme unité minimale d’une grammaire vidéoludique ?

Random Thoughts

- Mutability of ludemes (cheating) is quite different between board and video games

- Game loop as ludeme;

while trueas a fundamental technique to enable video games in the first place - Something as seemingly easy as walking around needs quite some logic in code. There is also some reappropriation happening here, since the arrow keys were not intended to move around sprites. Insofar moving in a direction with an arrow keys could be considered a ludeme, although the grapheme bit unfolds in the difference of the avatars sprite to it’s surroundings (and maybe in a walking animation)

- The materiality of a grapheme can also be quite different from each other. Sometimes it’s bit a bitmap graphic, sometimes vector, or even calculated and generated on the fly by a drawing framework

Bibliography

Browne, Cameron. n.d. “Everything’s a Ludeme Well, Almost Everything.”

Browne, Cameron, Dennis J. N. J. Soemers, Éric Piette, Matthew Stephenson, Michael Conrad, Walter Crist, Thierry Depaulis, et al. 2019. “Foundations of Digital Arch{\ae}oludology.” arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.13516.

Hansen, Damien. 2023. Parler le jeu vidéo : Le ludème comme unité minimale d’une grammaire vidéoludique ? Parler le jeu vidéo : Le ludème comme unité minimale d’une grammaire vidéoludique ? Culture contemporaine. Liège: Presses universitaires de Liège. https://books.openedition.org/pulg/18941.

Hurel, Pierre-Yves. 2020. “L’expérience de création de jeux vidéo en amateur - Travailler son goût pour l’incertitude,” May. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/247377.

“Pierre-Yves Hurel : Le Jeu Vidéo En Amateur : La Création Comme Dégustation, Le Ludème Comme Prise Vidéoludique.” n.d. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://podv2.unistra.fr/video/25837-pierre-yves-hurel-le-jeu-video-en-amateur-la-creation-comme-degustation-le-ludeme-comme-prise-videoludique/.

“What’s a Ludeme?” n.d. Accessed September 19, 2024. https://www.parlettgames.uk/gamester/whatsaludeme.html.

See also

- Routine and Software Design Pattern

- Frustration, Conferences and Ludemes

- A handful of pixels of blood - Presentation Text and A handful of pixels of blood - Extended Abstract

- Observing the Coming of Age of Video Game Graphics

Footnotes

-

which is found similarly in Henriot, who makes the distinction “l’objet-jeu – le support matériel que des normes sociales s’accordent à désigner comme un jeu – et le jouer – qui désigne l’action ou l’activité de jouer” (Hurel, 2020, p. 193) ↩